Andrew Stuttaford does not like religious belief. I am sure he likes some religious believers, and some of them are, doubtless, among his best friends. Yet in National Review Online, he makes it clear that the blasphemous movie "Life of Brian" is a Gospel to him.

"The Corner," NRO's blog, is turned over to Stuttaford on most weekends, where he vents about two topics: health puritans, and religious believers who won't get with the secularist program. I am with him on the first point, though his attacks on the no-smoking-and-drinking crowd are tiresome by now.

The second point is the key to his thinking, at least the thinking he contributes to NRO. Stuttaford seems to loathe -- the word does not seem too strong -- the beliefs of Islamists, Evangelicals, and religious believers of all stripes, probably in that order. For instance, he does not merely disparage radical Islamist clerics in his native Britain because they incite murder and undermine civil society. He thinks they need to shut up because the U.K. is a secular nation, and their God-talk has no place in the modern world.

An exaggeration? Here are his words of praise for "Brian": "If there's any type of belief that runs through the movie, it's disbelief, unbelief, a world-weary skepticism." Stuttaford means this as a compliment, though the world needs more skepticism the way it needs more genocide.

"The real target of the movie's satire is not religion as such, but the unholy baggage that too frequently comes with it — the credulity, the fanaticism, and that very human urge to persecute, well, someone." I could make the same case about sports fans or science-fiction devotees. Since the Enlightenment unleashed its monstrous crimes, all for secular reasons, religion is a distant second to politics as a raison d'abattre. I've seen drunks come to blows over perceived slights -- and religion is a primary cause of "unholy baggage"? Not human frailty?

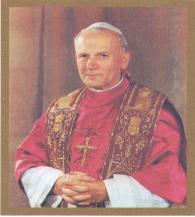

Given the massive failure of secularism to make people happy, whether through ascetic utopian scemes (Marxism) or wretched excess (consumerism), it's touching that Stuttaford can maintain his faith in it. To maintain his beliefs, he takes aim at easy targets like Scientology or Jerry Falwell, avoiding more formidable targets like, say, Confucianism or Catholicism, which have vast intellectual traditions that don't fit into his model of religion as "superstition."

He continues: "There's a lovely moment when, appalled by the spectacle of the faithful gathering beneath his window, he tells them that, 'you don't need to follow me, you don't need to follow anybody. You've got to think for yourselves, you're all individuals.' Simple stuff, but, these days, pretty good advice."

But we're not "individuals" in the sense that we are radically separated from everyone else. We rely on others to grow our food, make our electricity, build our houses, and most other necessities. None of us has invented our worldview out of whole cloth; we choose what we believe (hopefully) based on whether it is true or false.

Our species is more interconnected than it has ever been, yet some persist in thinking that we can somehow be "individuals" in the most literal sense. Yet the more disconnected people are, the more miserable they become. When entire societies embrace that philosophy, they begin a slow march toward oblivion, just as Britain and Western Europe's populations are slowly dying.

Belief in the unfettered self is the most superstitious belief of all, and the surest path to self-destruction.