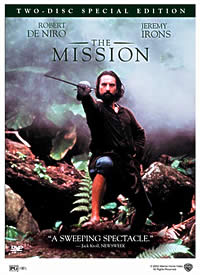

“The Mission,” Roland Joffe’s harrowing, fictionalized account of the evangelization and betrayal of native South American tribesmen, is finally available on DVD. I have not bought it yet, but it will be high on my Christmas list this year. Warner released it as a two-disc set with lots of goodies, including a “making of” special that I am eager to see.

![]() If you consider yourself a serious Catholic and have not seen this movie, you ought to schedule some time for it. “The Mission” has some of the most beautiful moments — visually and emotionally — ever put on film. Briefly, the story is about Father Gabriel, a Jesuit who brings the Gospel to the hostile natives who live in dangerous, inaccessible highlands above a waterfall. The slaver Mendoza also seeks out the natives, but to bring them back as chattel. When Mendoza finds out his brother has been sleeping with his mistress, he murders him.

If you consider yourself a serious Catholic and have not seen this movie, you ought to schedule some time for it. “The Mission” has some of the most beautiful moments — visually and emotionally — ever put on film. Briefly, the story is about Father Gabriel, a Jesuit who brings the Gospel to the hostile natives who live in dangerous, inaccessible highlands above a waterfall. The slaver Mendoza also seeks out the natives, but to bring them back as chattel. When Mendoza finds out his brother has been sleeping with his mistress, he murders him.

Dying inside with guilt, Mendoza accepts Fr. Gabriel’s offer of reconciliation and seeks the forgiveness of the natives. Instead of killing him, they accept him into their community.

Because of political machinations between European powers, the pope, and the Jesuits, the two men are ordered to withdraw from their mission (Mendoza joined the Jesuits to complete his abandonment of his former life.) They refuse their superior’s direct order to leave, remaining with the natives as soldiers approach to force them from their land.

Robert de Niro, as Mendoza, is the tortured centerpiece of the movie, and his performance reminds one of the power of film acting. I’ve seen the movie at least five times, and I am still reduced to tears at the moment when he realizes the natives have forgiven him. Jeremy Irons’s Fr. Gabriel is a convincing portrait of a genuine pacifist, a man who eschews violence but not because of physical cowardice (as the ending makes clear).

The only thing that detracts from the movie are the left-wing political references sprinkled throughout the movie, derived from Latin American Cold War politics in the 1980s. It was “topical” when it came out in 1986 because of the civil wars in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and other Spanish-speaking nations. Than man’s injustice to his fellow man is frequently manifest in politics, there can be no doubt; but in a movie like this, which derives its greatness from great themes of Western fiction — death and life, freedom and slavery, sin and redemption, obedience and conscience — transient politics intrude upon the work’s integrity.

There are other flaws: at the end of the credits, when the cardinal looks at the audience with an accusatory stare, as if we are responsible for these murders, is too heavy-handed. Some lines (written by the incomparable Robert Bolt) fall flat, such as when Fr. Gabriel gives a brief speech whose theme is “God is love” — a true statement, but a cliché as a sermon topic.

It occurs to me that you might be put off by these shortcomings, and I hesitate to write them in case it puts anyone off from seeing it (or seeing it again). You would miss other gorgeous scenes, like the crucified martyr falling down a raging waterfall, or Fr. Gabriel’s “preaching” of the faith through music and icons.

You would also miss having yourself prodded by the central theme of “The Mission,” which is that whether we fight with the sword or without it, faith must be strong enough to face down death, or it is unworthy of the name. At the heart of the film is the small, enduring belief that in a world smeared with ugliness and power-worship, beauty and goodness will ultimately triumph.

Author: Eric Johnson

Madeleine Albright, classy gal

Time, the once-great magazine that has shrunk to 12 pages a week, has an interview with Madeleine Albright on the occasion of her new book. Like every memoir by a former Clintonoid, I won’t read it — I tend to shy away from fiction — so I rely on articles and reviews to tell me what to think of it.

Reading the interview, I thought, “Was tact a disqualification for a job in the Clinton administration?” I don’t recall anyone from Bush the Elder’s gang going out of their way to trash the Clintons; maybe there were a few, but they didn’t make themselves as obnoxious as these people. We’re not just talking about mid-level appointees trying to make a name for themselves, we’re talking about cabinet members all the way up to Bill and his lovely wife, Bruno.

Back to Madame Albright: the interview is very short, but it’s packed with howlers, such as “President Clinton focused on terrorism from the start,” and “Frankly, if there was a President Gore, we wouldn’t be in this particular mess.” There are several other questionable statements, like “Iraq is in fact a breeding ground for terrorists” (more accurately, it’s a magnet for terrorists as few of them seem to be homegrown.)

One nasty answer particularly stood out —

(Q) Bush’s foreign policy started as “Anything But Clinton” in almost every area—the Middle East, North Korea, China. Now events have pushed it back much closer to your approach. Do you ever succumb to schadenfreude?

(A) No, I’m much too kind and generous a person.

Because I’m kind and generous myself, I will not point out that Madame Albright looks like Ursula the Sea Witch from “The Little Mermaid.” Instead, I will let you decide.

|

|

|

|

Uncanny, isn’t it?

(Original joke made in 1997 by Steve Schultz when Albright was named secretary of state. Photos edited by me. Original photos (c) ???? whoever owns them.)

The U.S. can do two things at once

I’ve been posting way, way too much lately, and I swear I’ll refrain for a while after today. However, I wanted to get in one last post.

In looking for something else, I found this article from New Zealand that encapsulates a couple of irritatingly persistant arguments about Iraq.

First, the idea that the U.S. has “sqandered” the “goodwill” of the “world” in the last two years. This guy says:

If, heaven forbid, there is another attack of September 11 proportions, there will not be the same sense of innocent incredulity heard worldwide when the Twin Towers fell, and still heard at the first anniversary. The ledger is even now.

Leave aside the moral equivalence between terrorists and anti-terrorists in the last sentence. “Innocent incredulity” wasn’t the universal reaction to the terror attacks. I recall watching Palestinians celebrate on the West Bank; I remember left-wing columnists writing their “but” columns. (“Sure, killing officeworkers and airline passengers is wrong, but we [pollute the environment/support Israel/fill in the blank].”) The world did not suddenly support American foreign policy on Sept. 12, 2001. They didn’t love us — they pitied us. There’s a wide chasm between the two.

Second,

Rather than resume the pursuit of Osama bin Laden, or the difficult, clandestine tasks of counterterrorism in unpleasant foreign places, the President chose a much easier target – an old foe he felt sure he could find in an already defeated and devastated country.

We are pursuing Osama, fighting terrorism in “unpleasant foreign places,” and a host of other things such as freezing bank accounts and disrupting communications — all at the same time. Why is it so hard to grasp that U.S. counterterrorism efforts can proceed at several different levels simultaneously?

The Democratic presidential candidates repeat this charge all the time. This is a crowd of people that wants the Federal government to do more and more with each passing year. Their party is responsible for making the Federal Government the size of Germany’s entire economy, with dozens of departments, bureaus, and agencies performing hundreds if not thousands of tasks at the same time. Yet our several national security entities can either depose the Iraqi dictator or find Osama — but not both?

—

That’s it for the serious entries. I’m going to find something funny to write about.

Civilian casualties in Iraq

[My apologies for again “repurposing” something I’ve written elsewhere. I was responding to the question about civilian casualties during the Iraqi war, and disputing a wildly inflated total of over 37,137 deaths.]

There is no way there were 3,581 civilian deaths in Nasiriyah, as reported by Wanniski. My Marine unit had teams attached to most of the infantry forces in the city, and they did witness several dozen civilian casualties, many of them fatal. These occured mainly because the Fedayeen would do things like shoot from occupied buildings. That number of deaths could have only resulted from either intense artillery bombardment or a concentrated air campaign. Neither one happened.

Additionally, we spent a month in Kut, and went all around the city talking to civilians (that’s a big part of our peacetime role). There was no widespread destruction, and we met few people who had lost family members. In a city of 200,000, Wanniski’s reported figure of 2,494 is over 1% of the population. We would have seen some evidence — mass graves, lots of mothers in mourning, that kind of thing. We had teams in Diwaniyah, Hillah, and Najaf, and a dozen other places. No one reported mass deaths.

My team’s primary mission during the war, like that of all the other civil affairs teams, was to minimize civilian casualties by keeping them away from the fighting. This also let the commanders maneuver and shoot without fear of harming the innocent. I don’t think people realize the efforts the military made to avoid civilian casualties. In many cases, Marines and soldiers placed themselves at mortal risk to save innocent lives, or refrained from destroying an enemy position because civilians would be injured.

For what it’s worth, the Iraqis blamed the noncombatant deaths on Saddam for causing the war in the first place. They considered the losses unfortunate, but an acceptable price for getting rid of their tyrant.

[A dead link in this article has been removed. –admin, 8/4/14]

Not everybody is fighting terrorism

Michelle Malkin has a dead-on column about all the people who are impeding the war on terror at the local, state, and federal level. I would disagree that their resistance constitutes “spitting on their graves,” but it does endanger the living.

Last night on PBS (yes, I do watch PBS on rare occasions) they had a BBC special on Sept. 11, focusing on the government response to it. One of the things the Federal government did was seal the borders. I thought, “If they can seal the borders for one day, why couldn’t they do it every day?” They must have meant closing down border crossings. Whatever they did, two of the most significant things we could do are to seal the borders against illegal aliens, and deport illegal aliens who are here, with a high priority placed on countries that export crops of terrorists (Saudi Arabia, Syria, Colombia).

Neither one is going to happen, because the Bush administration doesn’t have the guts to stand up to the Diversity Uber Alles crowd. That virtually ensures another terrorist attack from foreigners. For the sake of their own sense of moral superiority, the Left, along with far too many irresponsible folks on the Right, has decided that any new law-enforcement measure is ipso facto one more move toward a police state. No matter how innocuous the plan, such as classifying air passengers by the risk they pose, the reaction is the same as if the feds abolished the Bill of Rights.

Some people apparently think that law enforcement is like a sport, and neither team should have a particular advantage over the other one. Like I said, this silliness isn’t limited to the Left.

David A. Keene, chairman of the American Conservative Union, worries that the computer screening program will go beyond its original goals. “This system is not designed just to get potential terrorists,” Keene said. “It’s a law enforcement tool. The wider the net you cast, the more people you bring in.”

Aaack! The cops might catch MORE CRIMINALS! Why, if this plan goes through, CRIMINALS MIGHT NOT EVEN TRAVEL BY PLANE ANYMORE! How will they get to visit their relatives in other states? Let us rend our garments.

(Our bishops aren’t too helpful here. Has anyone seen a statement from any U.S. prelate with even the mildest rebuke for immigration violators? Everything I’ve seen from the bishops says that all of our immigration laws are immoral, more or less.)

I’ve been mentally preparing an essay called “The emerging anti-anti-terrorism,” about the backlash against the war on terror. So much of this new phenomenon is identified as anti-war or anti-Bush activity, but we’re seeing an intellectual movement that is rapidly becoming an ideology. Just as the premise of anti-anti-Communism was that Americans had an “inordinate fear of Communism,” as Jimmy “Ask Me about My Foreign Policy Successes!” Carter put it, anti-anti-terrorists don’t think that terrorism poses a particular threat to the U.S., or at least not one we ought to get excited about. We’ll see if I get around to writing it. (Not that you probably care too much — I’m throwing it out there to see if it sounds interesting to anyone.)