Category: Uncategorized

Incoming missal

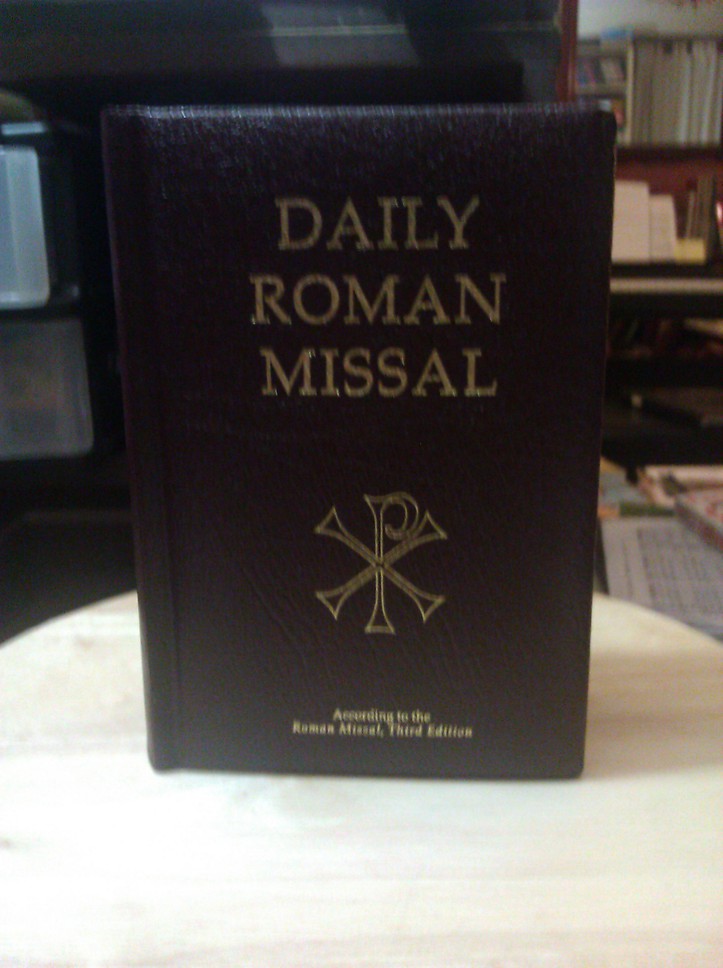

The attractive new edition of Daily Roman Missal

arrived at my mailbox yesterday.

arrived at my mailbox yesterday.

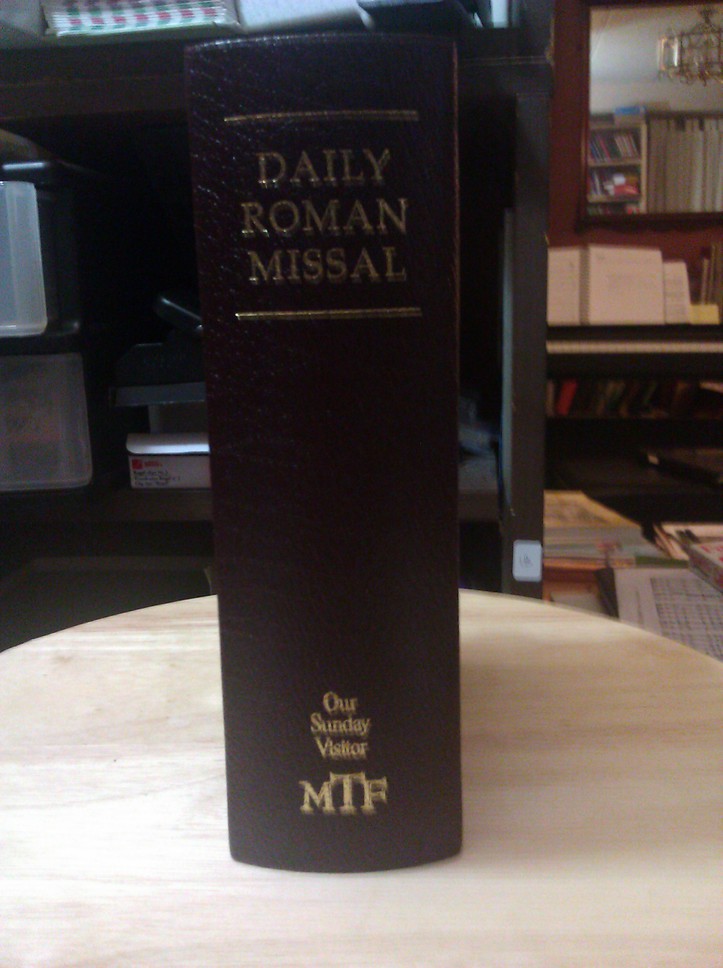

This is the seventh edition of Rev. James Socias’ hand missal which first appeared in 1993. It was issued by Midwest Theological Forum, the Opus Dei-related publishing house near Chicago, where Fr. Socias is vice president, and the book also bears the insignia of Our Sunday Visitor Press.

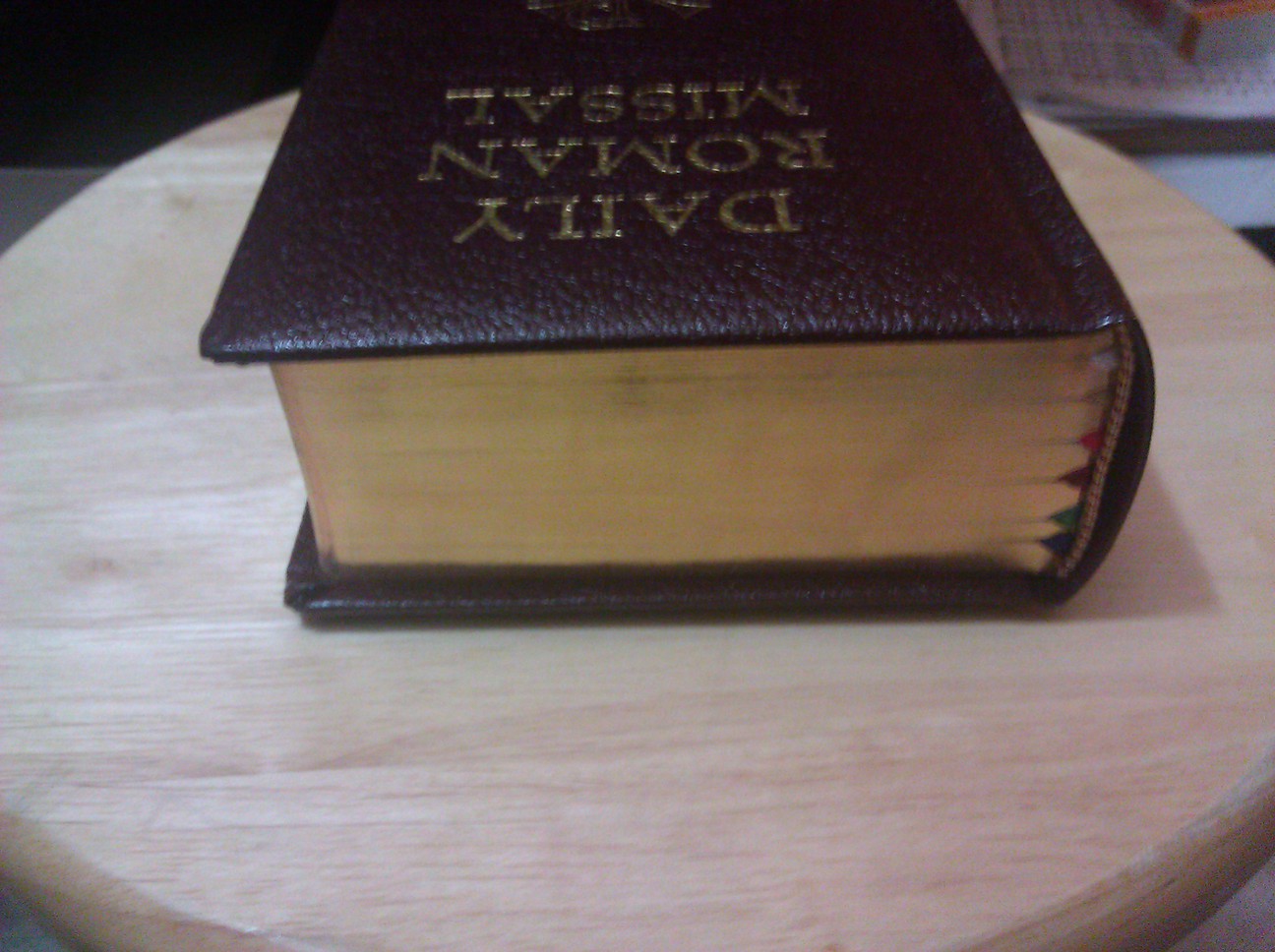

First of all, I’d say that the general build of the book is good: the leather cover has a padded feel, and the binding looks well-made. I don’t usually buy leather-bound books, but that’s the edition I was able to pre-order from Amazon (and for only $48), so I took it. (There are, incidentally, conventional hardbound editions too in black or burgundy, less expensive than the leather-bound versions.)

Now that it’s here, I feel like it’s a bit too nice for me to carry around casually as is my habit; I may have to save this for use at home, and get some simpler book that I can put into a tote bag with my other odds and ends for the drive to a weekday Mass at the mall chapel.

too nice for me to carry around casually as is my habit; I may have to save this for use at home, and get some simpler book that I can put into a tote bag with my other odds and ends for the drive to a weekday Mass at the mall chapel.

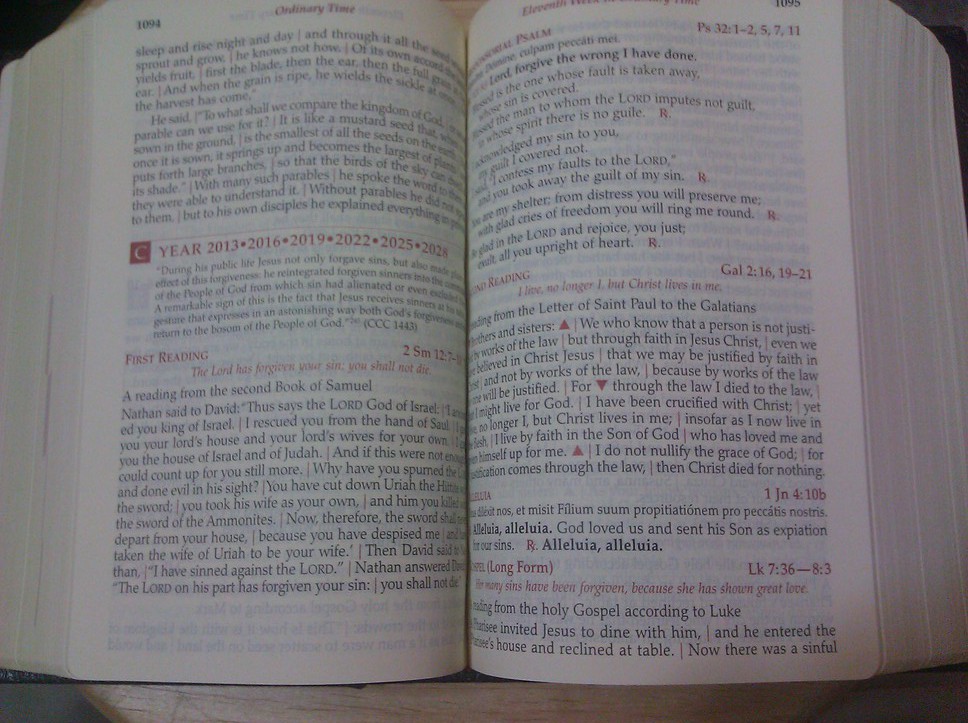

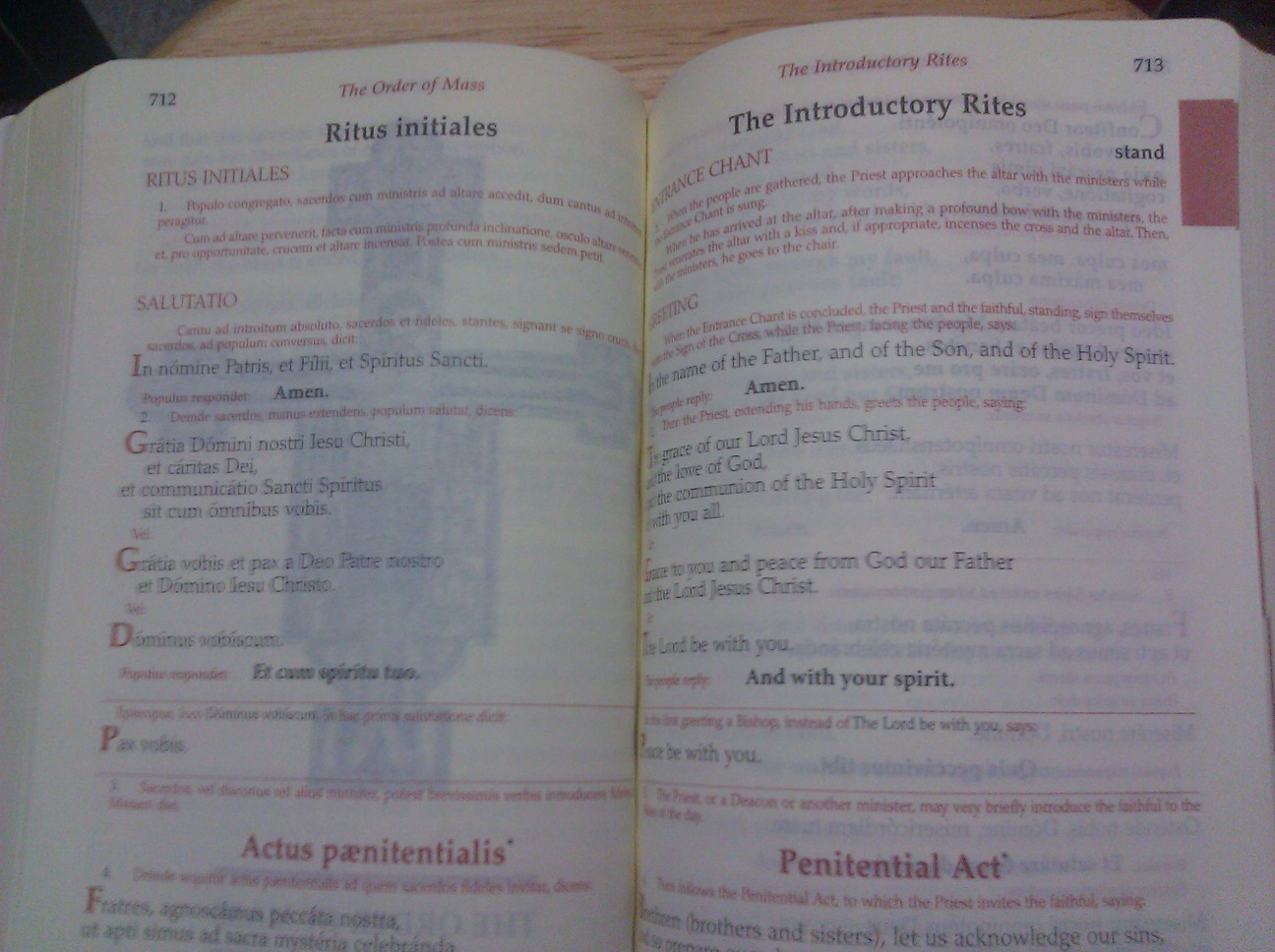

On the inside, the book contains full Scripture readings and propers, and I’m pleased to see that it includes Latin texts for the proper antiphons.  The typefaces are well-chosen, though the very nice bible paper does let text and artwork show through from the other side of the page, as you can see in the examples below; this detracts a little from the page’s readability.

The typefaces are well-chosen, though the very nice bible paper does let text and artwork show through from the other side of the page, as you can see in the examples below; this detracts a little from the page’s readability.

The ordinary parts of the Mass appear on facing pages, in the Church’s language and in the vernacular. I’m pleased to see the rubrics included too. The book has about 30 illustrations in its 2500 pages, which is not much. It would have been good to see more art. And they did have room for it: the book includes a little over 200 pages in devotional prayers.

The book has about 30 illustrations in its 2500 pages, which is not much. It would have been good to see more art. And they did have room for it: the book includes a little over 200 pages in devotional prayers.

A new priest blog

Fr. David Barnes, the fine pastor of St. Mary Star of the Sea Church in Beverly, MA, has launched a blog under the title A Shepherd’s Post, and I recommend it to you. I sang in his parish choir for the past few years, and appreciated his preaching and his encouragement of sacred music in the parish. Fr. Barnes is an active participant in the movement “Communion and Liberation” and serves as a spiritual director for seminarians at St. John Seminary in Boston.

Welcome to the Catholic “blogosphere”, Father!

Te Deum laudamus!

It’s the last day of the Church year, so it’s the perfect time to sing the Te Deum laudamus.

Here’s a recording of the Schola Cantorum of Milan. It comes with a display of the Gregorian score as found in the Graduale Romanum book (simple tone), so you can sing along:

But why stop there? Here’s an enormous force presenting the setting by Berlioz:

And the bold 1936 setting by Zoltan Kodály, written to commemorate the 250th anniversary of the liberation of Budapest from the Ottoman Turks:

Here, the choir of Notre Dame de Paris sings one of the Gregorian settings in the presence of Pope Benedict XVI. Notice a Notre Dame tradition at work: during some phrases, the choir is silent, letting the organ “sing”. As it happened, some members of the congregation, probably not familiar with the tradition, sang those phrases anyway. (And that’s OK: it’s a good thing that the congregation knew the Te Deum well enough to sing along!)

There are several Gregorian melodies for the Te Deum: simple and solemn Roman melodies, and simple and solemn monastic (Benedictine) melodies, so don’t be surprised if a particular chant performance doesn’t match a score in front of you. Do the Dominicans have their own melody, or the Cistercians? What about the Carthusians? Maybe some more versions will turn up!

A skeptical look at the population control movement

Professor Matthew Connelly (Columbia University) recently presented a radio documentary about the population control movement, “Controlling People”, on the BBC, in three episodes.

The story of a radical social-engineering campaign that began with high-sounding ideals and why it didn’t work.

Part One: The “religion” of Malthusian ideology: The self-interested Western desire to keep down rising populations in the Third World: population-control ideology spread by men in wealthy countries.

Part Two: The Indian Emergency: Mass sterilization camps in India in the 1970s operated on eight million people, induced by payments and imposed with government pressure and, later, force. Social scientist Steven Mosher, then a supporter of population control, tells about the methods of the one-child policy in China: government lock-up and coerced abortion. But the rise of working women led to delayed marriage and reduced fertility on its own.

Part Three: Continuing Incomprehension. Fertility rates are falling, but the population-control ideology of the 1970s remains, targeting the poor with sterilization. A surrogacy program in India exploits the needs of the poor to satisfy the wishes of Western couples. “The disappearing female child” targeted by sex-selection abortion and infanticide. The continuing conflict among pop-controllers between advocates of sterilization and contraception.

I should note that there are some biases in the presentation: Professor Connelly frames the conflict as merely one between somewhat arrogant proponents of sterilization and more liberal supporters of voluntary contraception, and he treats voices of opposition to abortion and contraception as a “fanatical” religious element. Still, the presentation of the history and the issues is worthwhile.